The grappling submission often called the Achilles lock, straight footlock, straight ankle lock, botinha (in Portuguese) or ashi-hishigi in judo, is defined by the position of the foot, which should be wrapped around the aggressor’s arm with the top of the foot tucked on the armpit. In Brazilian jiu-jitsu, and although this finishing move had existed for many years, it wasn’t until 2010 that the gi facet of the sport truly embraced the botinha, which became one of the style’s most common submissions. This was largely due to the innovations brought in by Rodrigo Cavaca, after his time spent in the US learning footlock techniques from Roli Delgado and Max Bishop, the later one a Hayastan footlock expert.

The History of the Straight Ankle Lock/ Achilles Lock/ Botinha

The origin of the lock is not known, it was most likely a creation of catch as catch can, as it was not a recognized technique of the Kodokan (judo’s original institution and the headquarters of the worldwide judo community), although it is sometimes seen in demonstrations and mid-20th-century footage.

There is a common understanding that in Brazilian jiu-jitsu, foot locks were frowned upon in the early days and this is partly true as the majority of academies gave (and give still) more emphasis to advancing positioning, chokes, and arm lock submissions other than foot attacks.

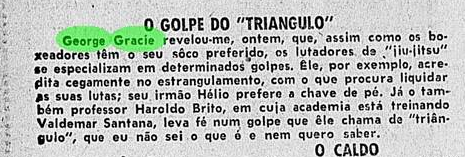

Contrary to common belief, Helio Gracie was in fact a fan of the straight ankle lock during his early vale-tudo (no-holds-barred) career, as shown on a news report from the newspaper “O Globo” back in 1932 (see image). In this small extract, the journalist goes over the favorite submissions of George Gracie, Helio, and their rival Haroldo Brito. Helio mentioning the ankle lock as his dearest.

Contrary to common belief, Helio Gracie was in fact a fan of the straight ankle lock during his early vale-tudo (no-holds-barred) career, as shown on a news report from the newspaper “O Globo” back in 1932 (see image). In this small extract, the journalist goes over the favorite submissions of George Gracie, Helio, and their rival Haroldo Brito. Helio mentioning the ankle lock as his dearest.

A more outspoken fan of the footlock in the Gracie family was Rolls Gracie (1970’s), who had in the toe hold one of his strongest weapons, and before him, there is also mention of Oswaldo Fadda‘s use of foot locks during the 1950s. Much like the toe hold, and although they were both popular for a short period a long time ago, it took years for the straight ankle lock to truly sink into the jiu-jitsu gi culture.

In no-gi the foot locks were assimilated sooner, especially once the ADCC (no gi’s most prestigious tournament) opened it’s doors in the late 1990s, exposing more Brazilian grapplers to foreign competitors in a submission wrestling environment, this way popularizing the no-gi aspect of the martial art, one more prone to foot attacks.

The surge in straight ankle lock attacks in the world of competitive jiu-jitsu (gi), which came in the early 2010 decade, was largely owed to the success of Rodrigo Cavaca and his students who brought great innovations to the sport’s mainstream, especially from the 50/50 guard, adding a lapel grip (instead of the old hand on shin-hand on the wrist). This “new” control allowed the attacker enough mobility to drive away from the foot and turn the submission into an attack to the top of the foot, instead of the Achilles tendon.

These innovations originated in the United States, where Cavaca spent some time, more precisely at West Side MMA Academy in Arkansas during 2009. Rodrigo explained:

I went to give a seminar in Arkansas at Roli Delgado’s academy, an American black belt that participated in one of the first editions of TUF (E.N.: The Ultimate Fighter). After the seminar, we were sparring and he sunk in a straight ankle lock holding his lapel. I saw it getting tighter but I didn’t believe he could tap me, he was only 70kg and I have pretty flexible feet. After we finished sparring, and after he popped my foot (laughs) I asked him how he had done it. He taught me some details and said he learnt it from a footlock specialist he knew. – Rodrigo Cavaca

That footlock specialist was Max Bishop a former student of Gokor Chivichyan who is himself a student of Gene Lebell. Gokor is well known for his work having produced high-end MMA fighters such as Manny Gamburyan, Karo Parisyan, and even Ronda Rousy through his style of grappling which Chivichyan calls Hayastan (a combination of sambo, judo and catch as catch can).

Roli worked with Cavaca for many days and even asked Bishop to come by the gym. Max and Cavaca spent 5 hours exchanging ideas Rodrigo recorded everything on camera. Cavaca worked carefully with Delgado, adapting this footlock game to the gi, Rodrigo’s own style, and to the rules applied by the IBJJF, jiu jitsu’s main governing body, for this Roli Delgado’s continuous input was also extremely important as mentioned by Cavaca to GracieMag in 2010.

Through a game highly reliant on foot and knee attacks Rodrigo and his students prospered and became one of the strongest gyms on the planet, producing world champions and medallists at the highest stage, including Cavaca who won the world championship the following year (2010), defeating 3 of his opponents (including the final) via straight ankle lock.

Cavaca’s sporting success and the surge in the use of the 50/50 guard set the tone to the popularity of the botinha, which grew exponentially driven not only by Cavaca’s students but also being adopted by rival teams.

- Rodrigo Cavaca

- Dean Lister

- Renato Cardoso

- Felipe Pena

- Luiz Panza

- Victor Estima

- Nivaldo Oliveira

- Marcus Almeida

- Caio Terra

Ashi-Hishigi in early Judo

Dean Lister showing the straight ankle lock

Rodrigo Cavaca showing the botinha lock

Rodrigo Cavaca vs Roberto Abreu

Nivaldo Oliveira vs Igor Ribeiro

Renato Cardoso vs Anderson Cyborg